How can you ensure you are not missing the boat on innovation, while managing the risk associated with it with as much confidence as possible?

The good news is, you can apply the scientific method combined with some powerful frameworks to not just manage a portfolio of innovative business models, but also manage the risk each of them presents — and all this inside of a corporate context, with intrapreneurs.

So how do you manage and measure innovation risk?

An approach to measuring innovation

Measuring innovation is a tricky business. Most corporate innovators know how deadly the demand for ROI can be for early stage innovations. The key seems to be, to have the right KPIs at the right stage of the process.

A couple of years ago I saw Alexander Osterwalder, the originator of the Business Model Canvas (BMC) speak in Berlin about his upcoming book on measuring innovation.

Osterwalder picked up on the topic of the ambidextrous organization first introduced by Robert Duncan in 1976. Describing a corporate portfolio between exploration and exploitation he suggests that for exploration the primary metrics should be focused on reducing innovation risk.

Using the gold standard of Desirability, Viability, Feasibility first introduced by IDEO, Osterwalder suggested assigning a percentage to each (baselining at 33%), and focusing on reducing risk in each category:

- He tied desirability to the quality of the value proposition (problem — solution fit), in addition to customer acquisition (channels in the BMC), and retention (Customer Relationships in the BMC).

- Feasibility was composed of resources, activities, and partners in the BMC respectively

- Viability he focused on profitability, i.e. revenue and cost

In each of these areas, a new innovation initially starts off with assumptions to be turned into hypothesis and tested. The amount of assumptions and untested hypotheses then comprised the total innovation risk for that area.

[For a great distinction between assumptions and hypothesis, see our colleague Tristan Kromer’s article]

Osterwalder’s approach made a lot of sense.

Both from a corporate portfolio perspective, as well as from how to measure innovation risk and reduce it in the process of moving projects from exploration to exploitation.

Expanding the Model

There were a few things this sparked for me, where I think his work can be expanded upon — especially for purpose-driven intrapreneurs:

- Using the horizon model vs. just a binary ambidextrous model to create a more granular business model pipeline and an active dynamic portfolio (of course, the three horizon model can be expanded upon as well)

- Leveraging the special role of the intrapreneur and understanding the importance of purpose (here more on why purpose is crucial for intrapreneurship)

- Integrating that purpose-driven businesses operate better

- Considering impact essential in a world of transparency

Creating a business model pipeline

Managing a business model portfolio across horizons allows organizations to discover and explore new opportunities early, & mature them while reducing innovation risk through running calculated experiments.

Customer validation and co- creation provides not just early feedback during development, but also creates market pull and sales opportunities as the idea evolves into a business.

Through a horizon model, innovation can occur on any stage and at any level of disruption.

Leveraging the special role of the intrapreneur

Intrapreneurs are a special breed. Not just employee, not quite entrepreneur, they create novelty from within existing structures and dynamics. This requires slightly different capacities than required for an entrepreneur, and makes purpose crucial. Their motivation and endurance, their resilience in the face of structural and cultural barriers to innovation that exist in any established company, will be as crucial of a factor in bringing the innovation to bear as the acceptance in the market.

Integrating that purpose-driven businesses operate better

Purpose doesn’t have to be something world-changing. Over the years research does show, however, that purpose-driven businesses operate better: Meaningful Brands outperformed the stock market by 206% between 2006 and 2016 according to a study by the Havas Group. In a study by Harvard Business Review, it also showed that prioritizers of purpose outperformed developers and laggards in innovation and continuous transformation — aspects all groups considered essential for the today’s business focus.

Considering Impact essential in a world of transparency

Impact has become a bit of a buzzword recently. I prefer to keep it simple and assume that everyone has impact — good or bad. Whether I create life-saving infrastructure in a region or pollute it with toxins — it’s impact. The good news is that in a world where brand and purpose become transparent, organizations can no longer afford negative impact. There is a growing expectation for companies to measure success beyond financial results: 87% of consumers believe companies perform best over time if their purpose goes beyond profit (Source EY).

Sustainability has in many organizations become the new normal, and social impact for the bottom of the pyramid presents massively lucrative opportunities — after all, our current formidable challenge is how to lift six billion people above the living standards of the luxurious West, while making that sustainable.

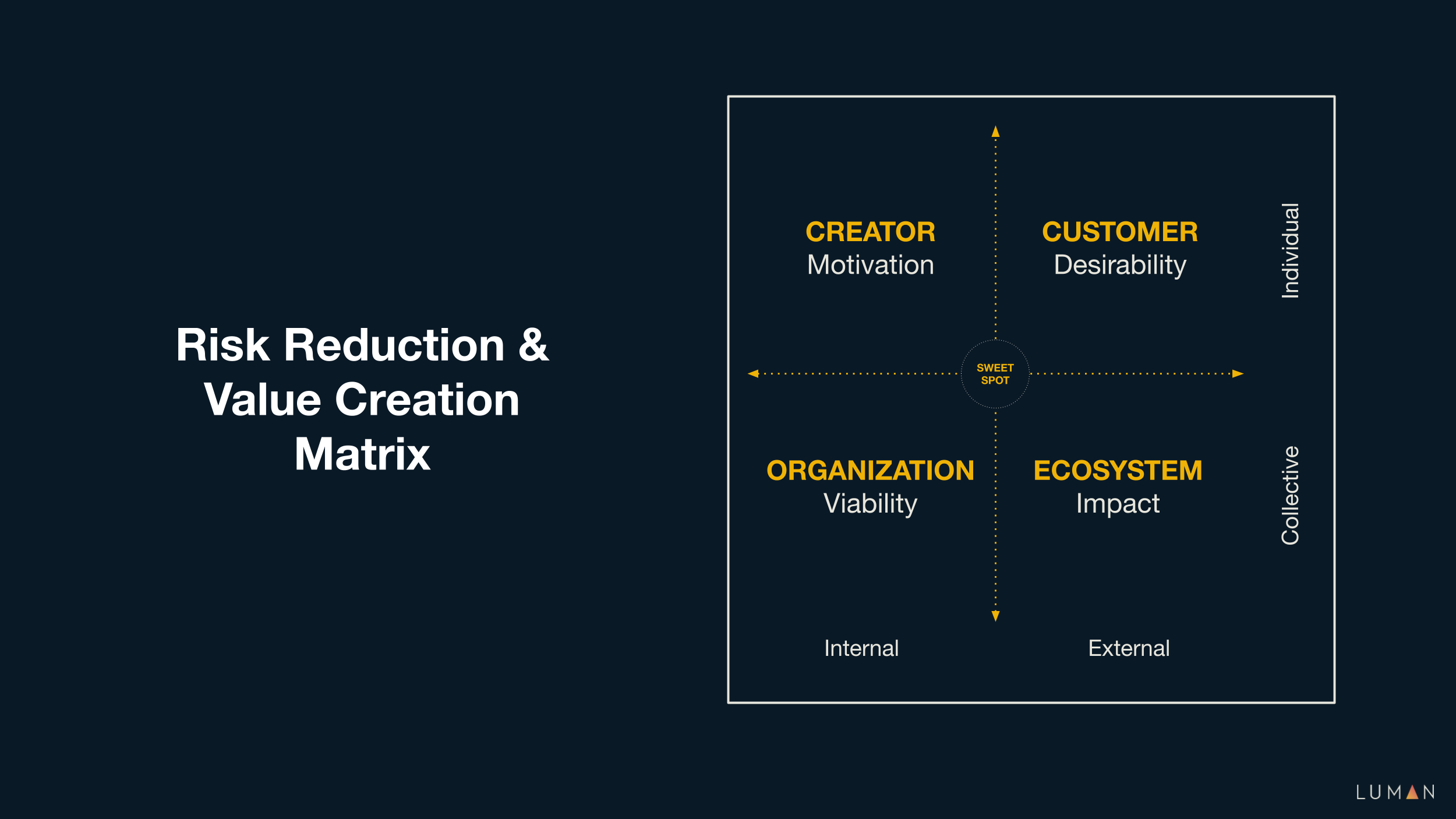

Putting the intrapreneur, the customer, the ecosystem and the business itself together, then provides us with four different areas of risk for our new innovation.

A Risk-Reduction Matrix for Purpose-Driven Intrapreneurship

One generic framework that can be applied to multiple scenarios is Ken Wilber’s All Quadrants all Levels — AQAL, which serves as one of the foundations for integral theory. Over the years, we have used this framework in a variety of contexts to test for cohesion and comprehension.

The basis of the framework are the four quadrants based on two dimensions: individual and collective, and internal and external (Wilber uses interior and exterior).

Putting all this together provides us with the four quadrants of the Intrapreneurial Risk Reduction Matrix:

- Internal Individual: The Intrapreneur and their Motivation

- External Individual: The Customer and the Desirability of the solution

- External Collective: The Impact on the Ecosystem if customers use the solution

- Internal Collective: The Business and the Viability of the solution as an offering

Overview

Intrapreneur + Customer = Who

The overlap between the intrapreneur and the customer gives you the who. Purpose is a big topic to approach. By focusing on a person, the problem becomes, well, personal. By means of empathy it creates the emotional connection between the intrapreneur and the future customer. As humans, we value our relationships. Creating a bond between the intrapreneur and the persona in question will provide intrinsic motivation in times when others might give up.

Customer + Ecosystem = Why

The bigger Why as to why a project matters to the world is in the overlap of the customer and the ecosystem. If customers now begin to behave in new ways due to the solution the intrapreneur is bringing, how does that impact the ecosystem? Being clear on whole system impact will ensure there are no blind spots or surprises. Integrating other players early will ensure the solution is adhering to a common purpose.

Ecosystem + Business = How

The overlap between ecosystem and business provides the unique positioning within the ecosystem. What is the unique value your organization compared to other actors in the ecosystem? How do you relate to competitors, startups, NGOs and governmental bodies? How are you differentiating and integrating?

Business + Intrapreneur = What

Finally, the overlay between the business and the intrapreneur is what the intrapreneur can make happen within the organization. What pull, what access, what executive and non-executive support exists for the intrapreneur? Are there already pathways for new business models? What are steps to make a new idea a reality within the organization?

Who/ Why/ How/ What for each Quadrant

Nature seems to be fractal in nature, i.e. the same building blocks create ever more complex systems. Conversely, we can use core frameworks up and down the levels we are looking at. In this case, while who/why/how/what applies for the overall quadrants, the same questions apply in each quadrant as well.

Motivation

One key risk element that is often taken for granted is the motivation of the individual intrapreneur. Both entrepreneurship and intrapreneurship require exceptional amounts of resilience. While entrepreneurs have the potential of a massive financial reward, intrapreneurs need to rely on a strong intrinsic motivation. Without that, they typically have little incentive in most organizations to develop an idea into an actual business, on the contrary, they will face plenty of opposition in structural and cultural barriers.

To address this risk, it is important to be clear and test for key indicators for each individual:

- WHO are you as an individual and who are you becoming? — Understanding self as source of culture and transformation, learning about key elements like self-reliance, self-expression, self-management and self-organization.

- WHY are you here? — Connecting to personal purpose. What matters? Where is a deep emotional connection to someone out there?

- HOW do you want to contribute? — What kind of legacy do you wish to create? What do you want to be known for? Who do you want to be known as?

- WHAT signals do you see that excite you? — What do you see out there? What trends? What customer needs that could be fulfilled better, or which might not even exist (yet)?

Desirability

The most crucial component beyond whether an individual has the resilience to become an intrapreneur is of course, the actual desirability of the solution. Here we enter standard value proposition design:

- WHO is your customer? — The real starting point of any good business. There has to be someone you care about and whose life you want to improve. The clearer you are on your customer profiles, the better you can serve them.

- WHY do they have an issue? — What is the job they need to get done? What would be potential gains that would make their lives better? What are some of their most crucial pains?

- HOW are they getting the job done today? — is there a solution out there already? What works about it? What doesn’t work about it? What do people love? What do they hate about it?

- WHAT would make their life easier? — What value could you provide? What would get the job done easier/ better/ faster? What gains can you create? What pains can you relieve?

Impact

No business operates in isolation. Around every customer and their lives is an entire ecosystem. One risk area is not understanding how you integrate into the ecosystem, whether it be because of a competitor, of government regulations, of an NGO that has a contrary cause, or other players in the ecosystem from startups to — in today’s world of Instagram fame— even individuals. It is crucial to understand how you distinguish yourself and how you can enroll allies in your cause.

- WHO in your ecosystem cares about this? — Are there startups out there who do something similar? Other companies? What causes are attached to your offering? Are there any NGOs you could co-operate with that overlap with your purpose? What is in the interest of local or international multi-lateral organizations?

- WHY do they care? — What are their motivations? Their jobs to get done and pains and gains?

- HOW are they addressing this today and what is emerging in trend lines? — How are they solving for this? Are there any novel areas evolving? Are there cultural trends that might affect this domain in the near future?

- WHAT impact could you create? — How would you measure how you are impacting the ecosystem? What are some of the metrics you could apply for your cause?

Viability

Finally, of course, the intrapreneurial project has to be a fit for the company. This goes both for strategic directions as well as capabilities, as it also addresses technical feasibility of the project given the company’s current brain trust, patents, and technological state. But nearly more so than that, it is about finding allies. About connecting to the internal network. Intrapreneurs typically face a lot of resistance. Structural and cultural barriers are all to common (hence the initial focus on the resilience of the intrapreneur). The intrapreneur will not be able to succeed alone. As the African proverb goes: “If you want to go fast, go by yourself. If you want to go far, go with others.”

- WHO else in your company cares about this? — Who would benefit if this project existed? Which other departments should get involved? Have their been similar projects in the past that you can learn from or leverage? Who is talking about similar ideas?

- WHY do they care? — Just as it is important to understand your customers’ motivations, it is crucial to understand what others in your company value. What is driving them? What is behind their activities? Where are overlaps in your motivation?

- HOW are they addressing this today? — Many large organizations suffer from silos and silo-thinking. Beyond the empire building, what are other departments doing about your idea? How could you integrate with their efforts?

- WHAT assets can you leverage to get your project launched? — Unlike an entrepreneur who is starting from scratch, as an intrapreneur you have access to a brain trust of other employees, a brand name, existing customers, distribution networks, vendors, intellectual property and patents, and, of course, budgets for innovation…

Conclusion

This matrix represents a framework for risk-reduction.

Each quadrant and its respective question provide an array of assumptions to be turned into hypotheses and validated. Reducing risk of innovation — while emotionally exciting for most of us — can be reduced to a science.

Ultimately, that is what a scientific approach to innovation is all about. A scientific approach is about measuring risk, about consciously managing a portfolio of potential and existing customer value, and of having ways to test, validate and learn continuously.

Innovation is not a burn-money-and-fail-fast approach. That idea, that innovation means you have to behave like a Silicon Valley software startup, does not work for a company that, e.g. provides mission-critical infrastructure that lives depend on.

Nor can organizations keep their head in the sand an play it safe. Because then they shall be obsolete before they know it.

Innovation is about making ideas a reality.

For that, you have to make sure that you align everything, the intrapreneur’s motivation, the customer’s needs and desires, your ecosystem impact and ultimately, the viability for your business.

And take some risks. Because without investing in the future, you will probably not have one…